current exhibitions

LUISA RABBIA

BEGINNING AGAIN

January 22nd-February 14th, 2025

A NEW BEGINNING?

From Lascaux caves’ proto-shamanic artists to Malevich

and Mondrian, Pollock and Warhol, there has always been an

end and a beginning in painting. In my beginning is my end, famously

wrote T.S. Eliot in the first line of the first of his Four Quartets, “East Coker,” September 1940. But for painting it’s also true the opposite—in my end is my beginning. Painting’s form has been ending with any major cultural shift in every advanced civilization, then constantly been reborn when a new social order demanded a different visual language. Ours is no different: the algorithm-defined social order being built by the techno-capitalist society requires a move from a physical, medium-based languages (paper, etc.) to

digital ones. Yet painting is resisting, if briefly, with the remnants

of a declining humanistic society and the emergence of new social subjects no longer kept out of high culture by race, class, and gender boundaries. By its very nature and history, art is created purely by human intelligence and emotion (pre-historically by a magical intent), even if the medium is not oil canvas paper stone metal but machinery. There is certainly no new beginning now, and not yet anew ending, just a necessary r’existence.

The Gods, Aftermath and The Gods, Beginning Again, the two works

being exhibited by Luisa Rabbia (both 2024, oil on linen, 96 x 72

and 96 x 60 inches respectively), evolve the imagery present in

her previous group of paintings, five precisely, created since 2023, starting with The Gods, Conundrum, which inscribes dominant aspects of society under the archetypes of ancient Greek mythology. The gods of Greek mythology, expressed as governing ever human event and emotion in the two great poems Iliad and Odyssey, constitute in fact the very beginning of what we historically consider humanistic Western culture. The ones specifically nominated in two of the artist’s paintings, Ares (the Latin Mars) and Artemis (the Latin Diana), much represented also in Renaissance and Baroque art, evoke major themes of human anguish today, wars

and the survival of the natural world.

In Aftermath, the gods still keep the world in a state of war. Paolo

Uccello’s red and brown spears from La battaglia di San Romano (circa 1440, Uffizi, Firenze) emerge straight and long from a crowd of humans/soldiers defined only by their heads and shoulders. The group standing upright, on the top half of canvas, denote those still alive after the battle while the heads upside down, on the canvas’ lower half, indicate those who are dead or barely surviving supported by sticks. The dominant colors, red and blue, mark the factions in conflict. Rabbia’s paintings are structured by a sort of visual shorthand, that lets the artist spread representational elements in a multi-space that has the flatness of abstract painting. At center, a surfacing hand indicates that, before any image is painted, the artist covers the entire canvas

with her handprints, not to mimic those covering pre-historical caves

but to build a texture where her body physically participates in the

work’s pictorial making. Along the conceptual median line dividing the representation in two adversarial colors, green fragments of a spinal column are abbreviations of the skeleton that signifies death. And at the top of the image, half of them red, the other half blue like the factions in conflict underneath, stand the heads of the gods, dotted by piercing eyes that dominate the battle’s aftermath. Inside the gods’ bodies, fully unified in a single circle, are crowding the fighting humans. Like in the Tibetan Wheel of Existence held by Yama, Lord of Impermanence, the soldiers gathered in the circle signify that life and death also characterize a humanity permanently at war with itself.

Beginning Again, with its predominant blue alluding to a state of peace, evolves the wheel of existence into an Edenic-like tree generated by the gods above. Inside the tree’s canopy grows, along with a smaller planet, the Earth populated by the living. Below, on a predella, rise like roots the upturned legs of the dead, designating a subterranean realm out of which a generation of the living is born again. It’s a conceptual map of the world, somewhat close to the theologized cosmography of Jacob Böhme. Rabbia’s constant juxtaposing of gods and humans, of living and dead, also recalls an archetype of early Twentieth century, Gustav Klimt’s Tod und Leben (Death and Life, 1908–11, Leopold Museum, Vienna). Here Death and the Living

inhabit the same space: Death as a menacing skeleton wrapped in

a blueish dress covered with crosses and holding a club; the Living

tightly embracing each other in fear across his phantom, forming an oval mass of women, men and children as if to reconfigure the primordial egg of creation. Precisely in an original, Orphic egg’s form is also shaped the world of the Living in Beginning Again. Under the

round, reddish gods at the top, inside the intensely blue of the oval egg, an Earth and a smaller planet have formed, teaming on their border with human heads shifting in color between red and blue, while in the center, next to a pair of arms/legs, a long spinal cord originating from the central god seems to burst out electrifying the planet.

Rabbia’s painting embodies and exalts a specific visual syncretism of our time. In the years 1910–1925 advanced, radical artists, exhausted by centuries of either religious or social narrative art, excited also by the notions of velocity and simultaneity generated by the machine and the industrial modes of production, moved toward abstraction to express a new sensorial and intellectual multiplicity of emotions, sometime guided by a religiosity without Gods, churches and doctrinal dogmas. Artists today, exhausted in turn by the erasure of physicality that a technological, digital inscription of

the world entails, appear to re-imagine representation as a strategy

to maintain a level of humanity in the survival of art. In The Gods.

Aftermath and Beginning Again, mimesis and abstraction collaborate

in creating the artist’s personal visual language where color, while

associated with meaning, is also independent from form. The figure

doesn’t obey to a social or natural referencing but creates its own psycho-iconic features. Representation, abstraction, conceptualization converge in founding the ‘sustainability’ of painting.

— Mario Diacono

Past exhibitions

Bauhaus ?

Opening Tuesday December 10, 5-7 PM

December 11-21, January 4-11

Wednesday-Saturday 12:00 to 6:00

Man in Space

Variations on a Bauhaus Theme

In 1931, in the midst of a divorce, Margaret Egloff, of Boston, moved to Zurich with her two children, to study with Carl Gustav Jung. As part of that psychoanalytic training, she painted about forty-five watercolors likely dictated by her dreams, as Jung’s practice required. For a short time that year, she had an affair with the novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald, whose wife Zelda was in a sanitarium in Zurich.

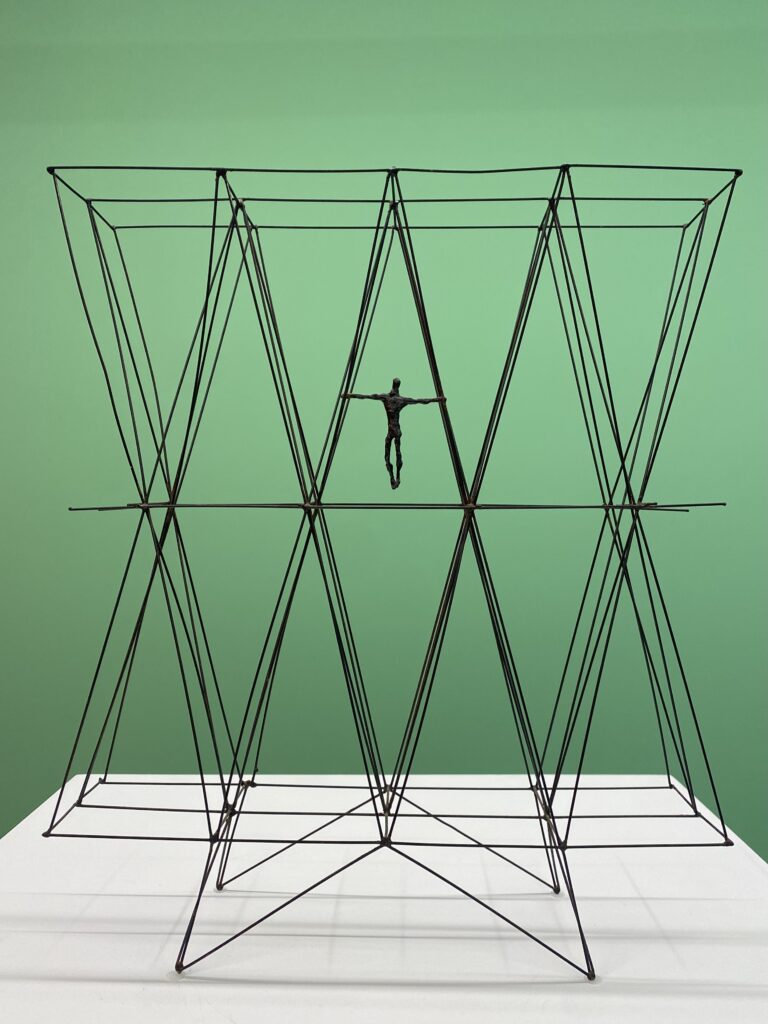

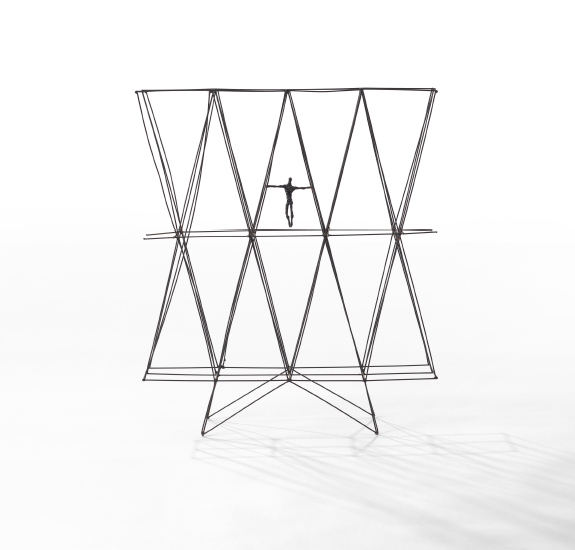

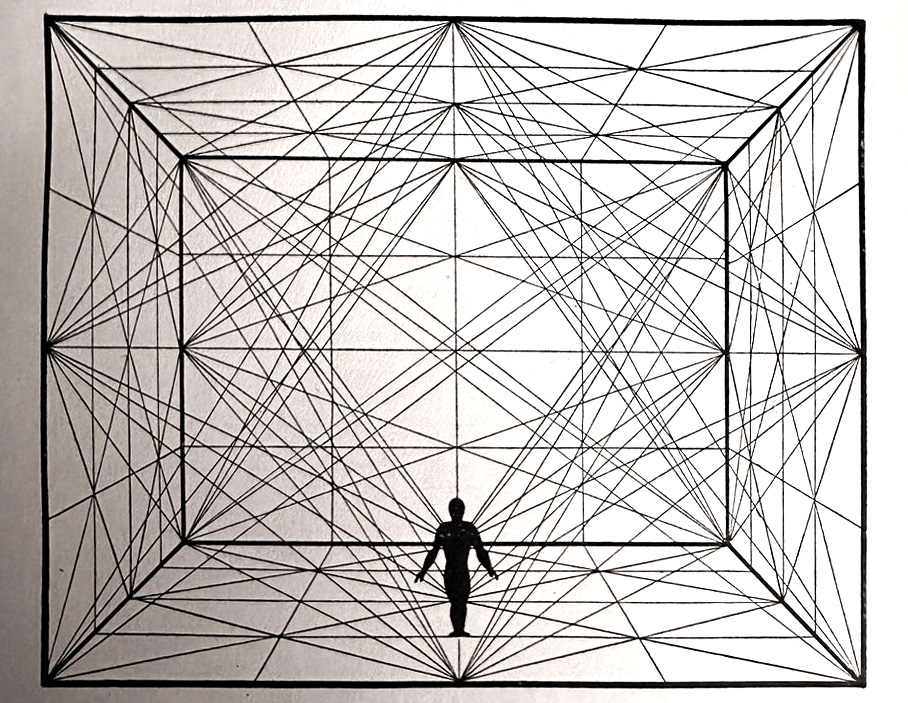

Margaret’s watercolors were discovered in a portfolio sometime after her death in 1998. In 2020 there also appeared in the estate of her son Frank a previously unknown sculpture, of metal wire; a sculpture extraordinarily similar to a well-known drawing by Oscar Schlemmer, reproduced on page 13 of the book he published with Laszlo Moholy-Nagy in 1924, Die Bühne im Bauhaus, as fourth in the series of the Bauhaus Bücher. No trace of such a sculpture has been found in either the Schlemmer or the Bauhaus archives, but given the incredible resemblance of this work to the drawing published in Die Bühne im Bauhaus, we tentatively propose that it was created within the circle of students or alumni of the Bauhaus, at about the same time as Margaret Egloff’s study with Jung in Zurich and her European travel with Fitzgerald. There is a profound logic to the possibility that she saw it and collected it, eventually giving or leaving it to her son, a psychiatrist as well. The Schlemmer image would have certainly appealed to a student of Jung, as the anonymous sculptor places Man at the center of an almost infinite abstract space, no longer that of a theater but rather of a universal system.

Die Bühne im Bauhaus

Bauhaus Bücher 4, Albert Langen Verlag,

München, 1924, page 13

As a variation on Schlemmer’s drawing, this singular sculpture strikes us as an expressionistic, symbolic representation of existential anxiety for the artist in between twentieth century’s two world wars, a meditation on the coming supremacy of industrial technology over the humanistic view of life.

At the same time, the sculpture also appears as the unexpected, unrecorded, physical representation of Schlemmer’s theory of a mechanized theatrical stage: “Man, the animate being, would be banned from view in this mechanistic organism. He would stand as ‘the perfect engineer’ at the central switchboard…” *: Leonardo’s Vitruvian man shrunk from microcosm, a measure of the cosmos, to mere function of a mechanized space, an appendix of the machine. Obviously Schlemmer used the word “Man” not in a gender-defining sense but as a shorthand for ‘Human’: when he creates a figure to perfectly activate the space of his Bauhaus stage, he names it simply “the dancer”, who can be either a man or a woman. But by placing the dancer’s figure at the center of a universal space rather than of the theatrical stage as it appears in Schlemmer’s drawing, the anonymous Bauhaus artist has radically changed the meaning of the images’ lines as spatial signifiers.

While Schlemmer’s drawing inscribes a three-dimensional space, this sculpture (whose dimensions are 18”x16”x5”)** clearly evokes, instead, the bi-dimensionality of the drawing itself. Further, by adding a graphic dimension to traditional sculpture, the work previews an early Minimalism. The anonymous artist doesn’t only follow the structure of Schlemmer’s drawing but also the spirit of the text accompanying it: on giving physical presence to “the cubical space” as an “invisible linear network of planimetric and stereometric relationships”, he builds a sculpture of pure geometry as we have seen it fully practiced in the early 1960s. In addition, by placing the human figure, molded in an expressionist mode akin to that of Alberto Giacometti’s works of the 1940s and 1950s, at the center of a universal space, he seems to follow Schlemmer’s coupling of the “laws of cubical spaces” with the “the laws of organic man […] invisibly involved with all these laws […] Man as Dancer (Tänzermensch). He obeys the laws of the body as well as the law of space: he follows his sense of himself as well of his sense of embracing space”, as illustrated in a drawing on the following page 14 of Die Bühne im Bauhaus. In not limiting him or herself as an epigone: the anonymous Bauhaus disciple pushes his master’s imagination further, making his work inspired by Schlemmer’s drawing not merely the illustration of an idea, but an idea itself, anchored not in the physical world but in a metaphysical realm.

Mario Diacono

*The Theater of the Bauhaus. Edited and with an introduction by Walter Gropius. Translated by Arthur S. Wensinger, Wesleyan University Press, 1961.

**As an accidental exercise in proportionality, it corresponds in inches to the dimensions of our exhibition space in feet.

Top image caption:

Artist unknown (Bauhaus circle?)

Untitled, circa 1924-31

Iron, 18 x 16 x4,5 inches

Provenance: (Margaret Egloff), estate of Dr Frank Egloff

Photo Julia Featheringill