current exhibitions

Jason Saager, Numinous Overcast

Opening Thursday, May 1st, 5-7 PM

May 1st-May 31st, 2025

Wed-Thurs 12:30-5:30 PM / Fri-Sat 1:00-6:00 PM

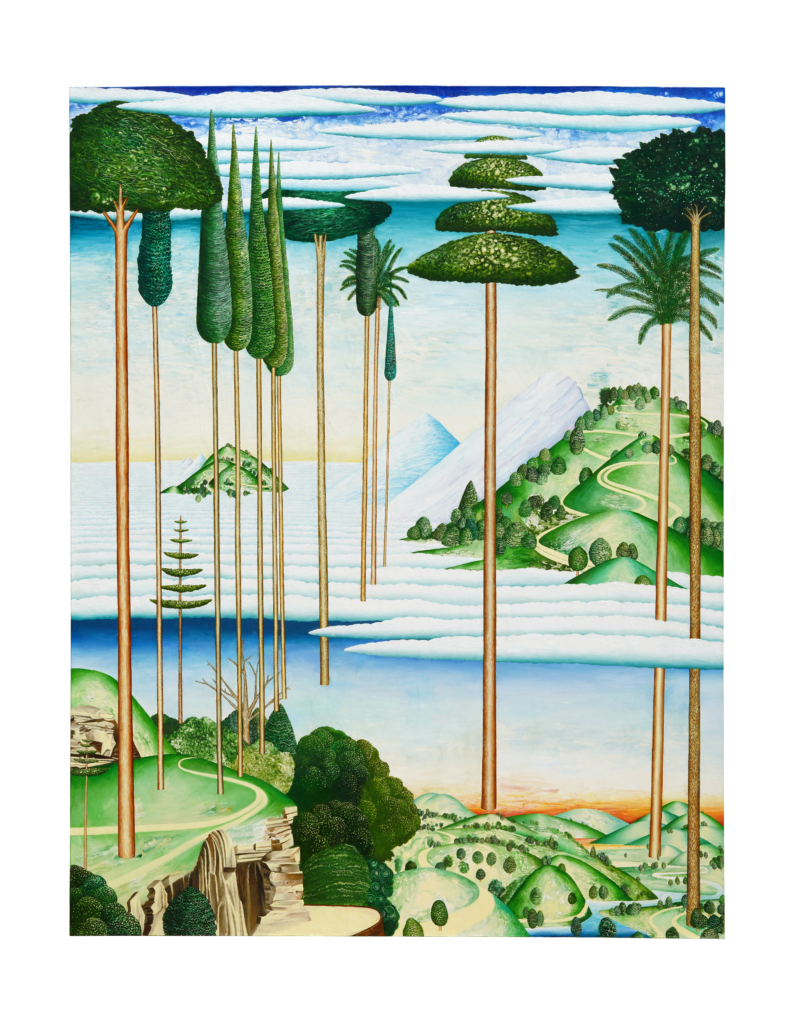

Numinous Overcast, 2025

monotype and oil on paper mounted over canvas on panel

48 x 62 x 1.5 inches

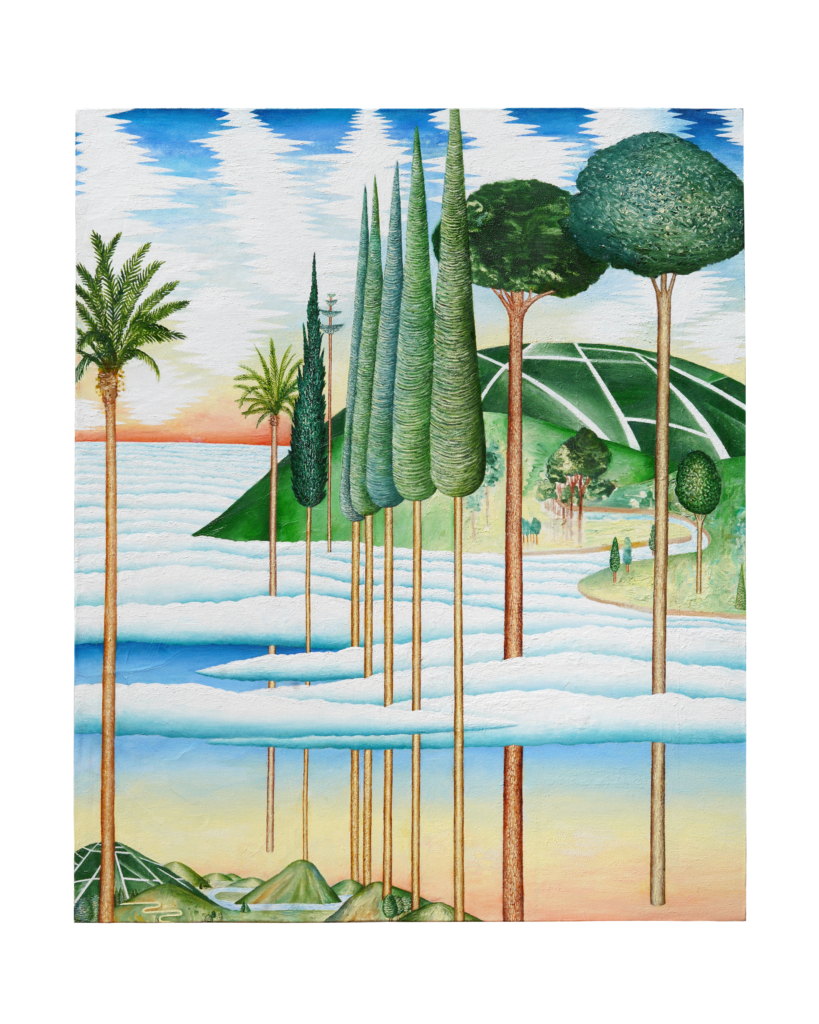

Ocean of Mystical Infinity, 2024

monotype and oil on paper mounted over canvas on panel

19 3⁄4 x 24 inches

Past exhibitions

Anna Conway, Instructions: Notre-Dame, Nursing, Pietà

Opening Saturday, March 1st, 4-6 PM

March 1st-March 29th, 2025

Wed-Thurs 12:30-5:30 PM / Fri-Sat 1:00-6:00 PM

SHARING THE SACRED

Issues from the hand of time the simple soul

T. S. Eliot, Animula, 1929

In the recent series of Anna Conway’s startling works whose iconographic Leitmotiv is directly carried in the first word of their titles, Instructions, the instructed subjects are animals. “Animals” contain the Latin word anima, the soul, and the trainers’ instructions to the animals in the paintings can be assumed to be as conversations of the artist with her soul. The fact that in the three small panels (each 12×12 inches) exhibited here the instructions/conversations take place in world-known sacred spaces, the cathedral of Notre-Dame in Paris and the basilica of Saint Peter in Rome, infers that since in the artist’s imagination (image in action) after mankind has wiped out itself the animals will inherit the earth, they will also become a new anima mundi. Anna Conway evokes a meta-reality, but she builds the representation of this meta-reality, millimeter by millimeter, in painstaking details, with a most intense realism. As in a true metaphysical painting, an extreme mimesis goes together with an extreme imaginal inventiveness: a world out of this world, a parallel world; mysterious ceremonies involving the meeting of human and animal actors or agents taking place with the backdrop of a religious space incongruous for such meetings. The religious places being iconic instances of Western art and architecture appear to be re-instatements of the sacred as metaphor of the religion of art. In Conway’s work there are no narratives, only events, her images are of epiphanies rather than of stories. In each of these three Instructions she packs more density of representation, more visual information per square inch than any other artist I am aware of.

Instructions: Notre-Dame, 2024

Oil on panel

12 x 12 inches

In Instructions: Notre-Dame, 2024, where the Parisian cathedral fits in all its details onto a square 12×12 inches surface as if seen under a microscope, the apparition of a green scaffolding (green is the symptomatic color in all the “Instruction” paintings a color that defines their iconographies), high up in the center of the nave, with trainers, hawks and owls going through their own sort of master classes, immediately deranges our expectations when visually entering the inside of a church. The artist even captures the time of the day, with the nave’s left side brightly lighted, the opposite side dark, and the sun shining through the stained-glass windows in the apse. The perspectival presentation of the cathedral’s interior magnifies the strangeness or simply the absurdity of the green platform in the foreground. This absurdity, however, owes nothing to Surrealism: it follows logically from an imaginary vision that the animals will inherit from mankind the sacred spaces of the earth. High over the platform, just under the cathedral’s ceiling, a camera is documenting the goings on the platform. One may ask, why teaching to animals the future in a gothic building? Here the animals are falcons and owls; four pairs of hooded falcons, just imported from the Arabian desert, rest over four pieces of railing in the middle of the platform, while two howls are grounded on the picture’s right, next to two hooded trainers masked as teaching howls; the falcons’ trainers instead, both kneeling, are one at the center the other on the left of the platform. Being birds, they have to be taught in a space with a huge distance between sky and ground, and Notre-Dame offers the ideal metaphor for a canyon.

The one other instance in contemporary art of an analogue theme is present in two paintings by Sigmar Polke, both from 1982 and with identical dimensions, 102 ½ x 78 ¾ : The Instructor (oil and resin on canvas, Collezione Maramotti) and The Copyist (dispersion and lacquer on canvas, former Macklowe collection). In these “magical” instruction paintings, the trainer appears as a supernatural being uttering a possibly numinous text that the copyist is seen writing down on a large volume, seated in front of a medieval city under a cloudy sky, the instructor’s utterings having unleashed in the atmosphere a tempest of colors (red, green, blue).

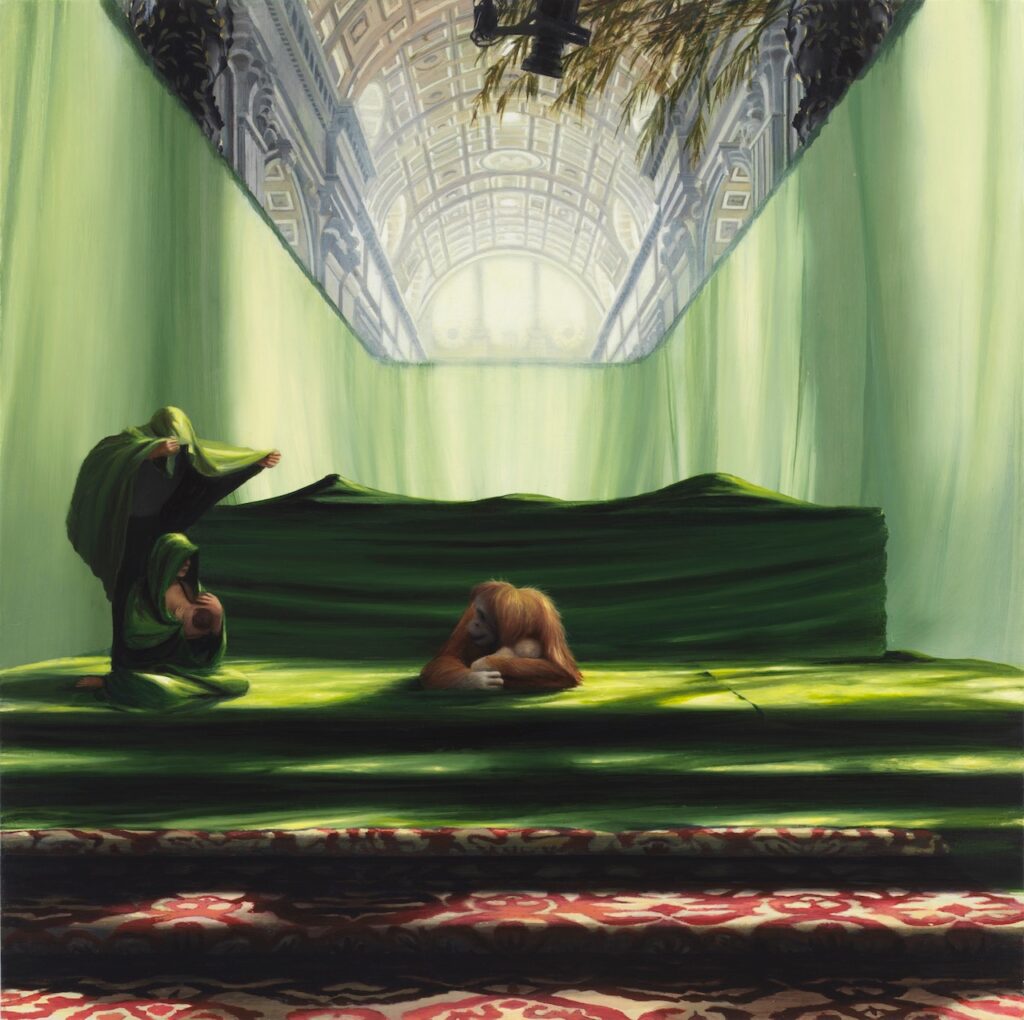

Instructions: Nursing, 2025

Oil on panel

12 x 12 inches

In Conway’s Instructions: Nursing, 2025, a teaching by mimesis takes place in St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, under Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s baldachin, in front of the church’s high altar. Both the baldachin and the altar are wrapped, like in a Christo & Jeanne-Claude’s monumental work, in green fabric, while a camera above films the event. On the left, a woman in green clothing is nursing her baby, on the higher of two steps wrapped in green fabric as is the entire Bernini’s sculptitecture, with the protection of a benevolent witch who, behind her, uses her mantle as a canopy alternative to the Bernini’s one, image borrowed from Goya’s Vuelo de brujas (Witches’ Flight). Across her, a monkey mom learns to nurse her own infant by imitating the human ways. This instruction thus evolves into a ritual for which a supernatural power is invoked in order to bring the trans-species learning into fruition.

Instructions: Pietà, 2025

Oil on panel

12 x 12 inches

A further mimetic training is posited in Instructions: Pietà, 2025. Here the artist, after reproducing with the same utmost fidelity she had mastered in re-creating Notre-Dame’s interior the lower half of Michelangelo’s Pietà in St. Peter’s Basilica, replicates the pietà (act of sorrow) by placing in front of the altar, below the sculpture, a dark vigorous, attentive yet melancholic horse being counseled or consoled by a woman, dressed and acting like a Madonna in a green mantle. Two arched white line converging from the opposite side of the image toward the kneeling horse, supposedly learning and acting like the Christ above him, institute the perspective that makes the viewer virtually participate in the suffering animal’s Christ-like passion. And like the monkey mom in Nursing, the horse is iconically adopted here for his symbolic power and traditional proximity to humans, as another being next in line to succeed humans’ defaulting on earth.

— Mario Diacono

Luisa Rabbia, Beginning Again

Opening Saturday, January 18th, 4-6 PM

January 22nd-February 22nd, 2025

Wednesday-Saturday 12:30-5:30 PM

The Gods, Beginning Again, 2024

Oil on canvas

96 x 60 inches – 244 x 152 centimeters

A NEW BEGINNING?

From Lascaux caves’ proto-shamanic artists to Malevich and Mondrian, Pollock and Warhol, there has always been an end and a beginning in painting. In my beginning is my end, famously wrote T.S. Eliot in the first line of the first of his Four Quartets, “East Coker,” September 1940. But for painting it’s also true the opposite—in my end is my beginning. Painting’s form has been ending with any major cultural shift in every advanced civilization, then constantly been reborn when a new social order demanded a different visual language. Ours is no different: the algorithm-defined social order being built by the techno-capitalist society requires a move from a physical, medium-based languages (paper, etc.) to digital ones. Yet painting is resisting, if briefly, with the remnants of a declining humanistic society and the emergence of new social subjects no longer kept out of high culture by race, class, and gender boundaries. By its very nature and history, art is created purely by human intelligence and emotion (pre-historically by a magical intent), even if the medium is not oil canvas paper stone metal but machinery. There is certainly no new beginning now, and not yet a new ending, just a necessary r’existence.

The Gods, Aftermath and The Gods, Beginning Again, the two works being exhibited by Luisa Rabbia (both 2024, oil on linen, 96 x 72 and 96 x 60 inches respectively), evolve the imagery present in her previous group of paintings, five precisely, created since 2023, starting with The Gods, Conundrum, which inscribes dominant aspects of society under the archetypes of ancient Greek mythology. The gods of Greek mythology, expressed as governing ever human event and emotion in the two great poems Iliad and Odyssey, constitute in fact the very beginning of what we historically consider humanistic Western culture. The ones specifically nominated in two of the artist’s paintings, Ares (the Latin Mars) and Artemis (the Latin Diana), much represented also in Renaissance and Baroque art, evoke major themes of human anguish today, wars and the survival of the natural world.

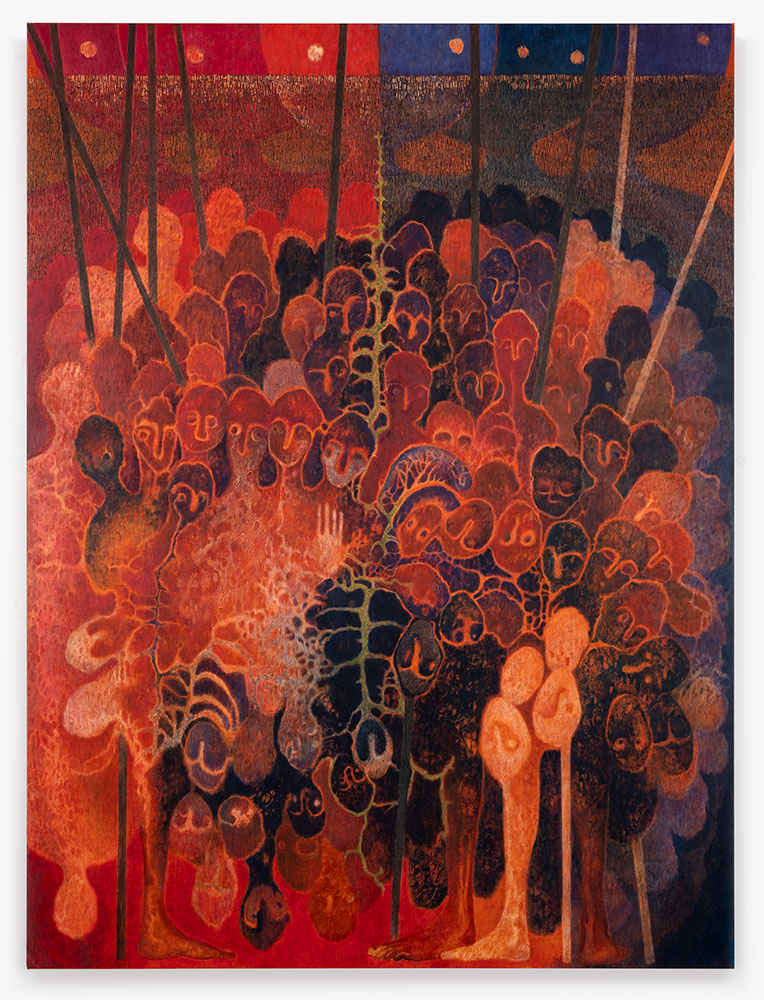

The Gods, Aftermath, 2024

Oil on canvas96 x 72 inches – 244 x 183 centimeters

In Aftermath, the gods still keep the world in a state of war. Paolo Uccello’s red and brown spears from La battaglia di San Romano (circa 1440, Uffizi, Firenze) emerge straight and long from a crowd of humans/soldiers defined only by their heads and shoulders. The group standing upright, on the top half of canvas, denote those still alive after the battle while the heads upside down, on the canvas’ lower half, indicate those who are dead or barely surviving supported by sticks. The dominant colors, red and blue, mark the factions in conflict. Rabbia’s paintings are structured by a sort of visual shorthand, that lets the artist spread representational elements in a multi-space that has the flatness of abstract painting. At center, a surfacing hand indicates that, before any image is painted, the artist covers the entire canvas with her handprints, not to mimic those covering pre-historical caves but to build a texture where her body physically participates in the work’s pictorial making. Along the conceptual median line dividing the representation in two adversarial colors, green fragments of a spinal column are abbreviations of the skeleton that signifies death. And at the top of the image, half of them red, the other half blue like the factions in conflict underneath, stand the heads of the gods, dotted by piercing eyes that dominate the battle’s aftermath. Inside the gods’ bodies, fully unified in a single circle, are crowding the fighting humans. Like in the Tibetan Wheel of Existence held by Yama, Lord of Impermanence, the soldiers gathered in the circle signify that life and death also characterize a humanity permanently at war with itself.

Beginning Again, with its predominant blue alluding to a state of peace, evolves the wheel of existence into an Edenic-like tree generated by the gods above. Inside the tree’s canopy grows, along with a smaller planet, the Earth populated by the living. Below, on a predella, rise like roots the upturned legs of the dead, designating a subterranean realm out of which a generation of the living is born again. It’s a conceptual map of the world, somewhat close to the theologized cosmography of Jacob Böhme. Rabbia’s constant juxtaposing of gods and humans, of living and dead, also recalls an archetype of early Twentieth century, Gustav Klimt’s Tod und Leben (Death and Life, 1908–11, Leopold Museum, Vienna). Here Death and the Living inhabit the same space: Death as a menacing skeleton wrapped in a blueish dress covered with crosses and holding a club; the Living tightly embracing each other in fear across his phantom, forming an oval mass of women, men and children as if to reconfigure the primordial egg of creation. Precisely in an original, Orphic egg’s form is also shaped the world of the Living in Beginning Again. Under the round, reddish gods at the top, inside the intensely blue of the oval egg, an Earth and a smaller planet have formed, teaming on their border with human heads shifting in color between red and blue, while in the center, next to a pair of arms/legs, a long spinal cord originating from the central god seems to burst out electrifying the planet.

Rabbia’s painting embodies and exalts a specific visual syncretism of our time. In the years 1910–1925 advanced, radical artists, exhausted by centuries of either religious or social narrative art, excited also by the notions of velocity and simultaneity generated by the machine and the industrial modes of production, moved toward abstraction to express a new sensorial and intellectual multiplicity of emotions, sometime guided by a religiosity without Gods, churches and doctrinal dogmas. Artists today, exhausted in turn by the erasure of physicality that a technological, digital inscription of the world entails, appear to re-imagine representation as a strategy to maintain a level of humanity in the survival of art. In The Gods, Aftermath and Beginning Again, mimesis and abstraction collaborate in creating the artist’s personal visual language where color, while associated with meaning, is also independent from form. The figure doesn’t obey to a social or natural referencing but creates its own psycho-iconic features. Representation, abstraction, conceptualization converge in founding the ‘sustainability’ of painting.

— Mario Diacono

Bauhaus ?

Opening Tuesday December 10, 2024, 5-7 PM

December 11-21, January 4-11, 2025

Wednesday-Saturday 12:00 to 6:00 PM

Man in Space

Variations on a Bauhaus Theme

In 1931, in the midst of a divorce, Margaret Egloff, of Boston, moved to Zurich with her two children, to study with Carl Gustav Jung. As part of that psychoanalytic training, she painted about forty-five watercolors likely dictated by her dreams, as Jung’s practice required. For a short time that year, she had an affair with the novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald, whose wife Zelda was in a sanitarium in Zurich.

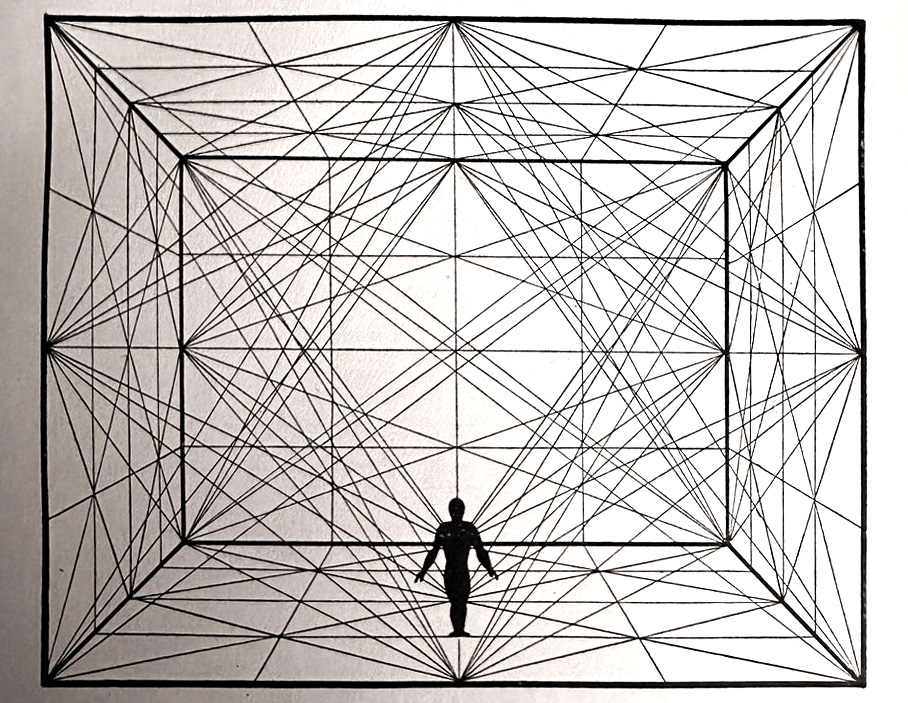

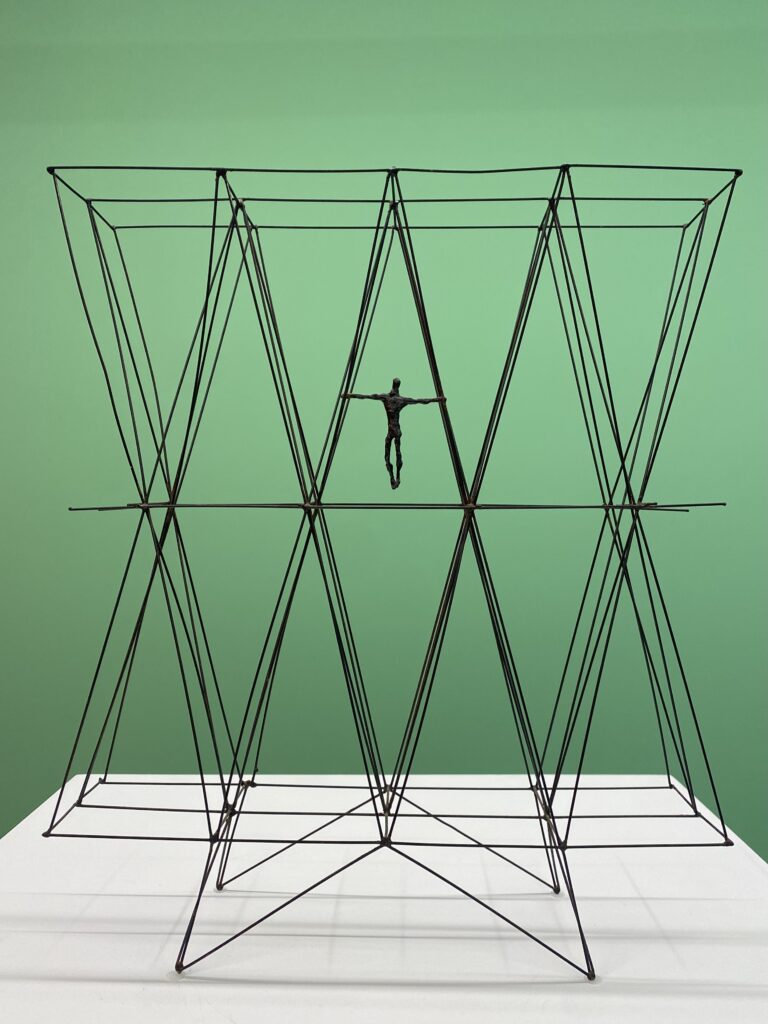

Margaret’s watercolors were discovered in a portfolio sometime after her death in 1998. In 2020 there also appeared in the estate of her son Frank a previously unknown sculpture, of metal wire; a sculpture extraordinarily similar to a well-known drawing by Oscar Schlemmer, reproduced on page 13 of the book he published with Laszlo Moholy-Nagy in 1924, Die Bühne im Bauhaus, as fourth in the series of the Bauhaus Bücher. No trace of such a sculpture has been found in either the Schlemmer or the Bauhaus archives, but given the incredible resemblance of this work to the drawing published in Die Bühne im Bauhaus, we tentatively propose that it was created within the circle of students or alumni of the Bauhaus, at about the same time as Margaret Egloff’s study with Jung in Zurich and her European travel with Fitzgerald. There is a profound logic to the possibility that she saw it and collected it, eventually giving or leaving it to her son, a psychiatrist as well. The Schlemmer image would have certainly appealed to a student of Jung, as the anonymous sculptor places Man at the center of an almost infinite abstract space, no longer that of a theater but rather of a universal system.

Oskar Schlemmer, László Moholy Nagy, Farkas Molnár

Die Bühne im Bauhaus

Bauhaus Bücher 4, Albert Langen Verlag, München, 1924,page 13

As a variation on Schlemmer’s drawing, this singular sculpture strikes us as an expressionistic, symbolic representation of existential anxiety for the artist in between twentieth century’s two world wars, a meditation on the coming supremacy of industrial technology over the humanistic view of life.

At the same time, the sculpture also appears as the unexpected, unrecorded, physical representation of Schlemmer’s theory of a mechanized theatrical stage: “Man, the animate being, would be banned from view in this mechanistic organism. He would stand as ‘the perfect engineer’ at the central switchboard…” *: Leonardo’s Vitruvian man shrunk from microcosm, a measure of the cosmos, to mere function of a mechanized space, an appendix of the machine. Obviously Schlemmer used the word “Man” not in a gender-defining sense but as a shorthand for ‘Human’: when he creates a figure to perfectly activate the space of his Bauhaus stage, he names it simply “the dancer”, who can be either a man or a woman. But by placing the dancer’s figure at the center of a universal space rather than of the theatrical stage as it appears in Schlemmer’s drawing, the anonymous Bauhaus artist has radically changed the meaning of the images’ lines as spatial signifiers.

While Schlemmer’s drawing inscribes a three-dimensional space, this sculpture (whose dimensions are 18”x16”x5”)** clearly evokes, instead, the bi-dimensionality of the drawing itself. Further, by adding a graphic dimension to traditional sculpture, the work previews an early Minimalism. The anonymous artist doesn’t only follow the structure of Schlemmer’s drawing but also the spirit of the text accompanying it: on giving physical presence to “the cubical space” as an “invisible linear network of planimetric and stereometric relationships”, he builds a sculpture of pure geometry as we have seen it fully practiced in the early 1960s. In addition, by placing the human figure, molded in an expressionist mode akin to that of Alberto Giacometti’s works of the 1940s and 1950s, at the center of a universal space, he seems to follow Schlemmer’s coupling of the “laws of cubical spaces” with the “the laws of organic man […] invisibly involved with all these laws […] Man as Dancer (Tänzermensch). He obeys the laws of the body as well as the law of space: he follows his sense of himself as well of his sense of embracing space”, as illustrated in a drawing on the following page 14 of Die Bühne im Bauhaus. In not limiting him or herself as an epigone: the anonymous Bauhaus disciple pushes his master’s imagination further, making his work inspired by Schlemmer’s drawing not merely the illustration of an idea, but an idea itself, anchored not in the physical world but in a metaphysical realm.

–Mario Diacono

*The Theater of the Bauhaus. Edited and with an introduction by Walter Gropius. Translated by Arthur S. Wensinger, Wesleyan University Press, 1961.

**As an accidental exercise in proportionality, it corresponds in inches to the dimensions of our exhibition space in feet.

Artist unknown (Bauhaus circle?)

Untitled, circa 1924-31

Iron, 18 x 16 x4,5 inches

Provenance: (Margaret Egloff), estate of Dr Frank Egloff